Last night, I had the occasion to speak with world-renowned hip-hop provocateur Boots Riley on a wide range of subjects spanning from his childhood in Detroit, spent in a household of Communist organizers, to his current work, organizing people in his neighborhood as a member Occupy Oakland. And, of course, we touched on his equally ground-breaking and ass-shaking music, and the 20-years that he’s now spent “using hip-hop to empower people” and “destroy Capitalism,” in bands like The Coup and Street Sweeper Social Club.

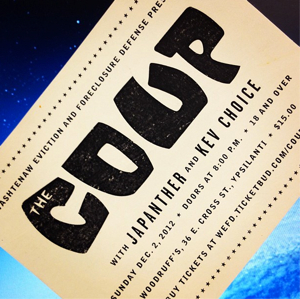

Riley and The Coup, as I suspect that most of you know, will be performing in Ypsilanti on Sunday night, headlining a fundraiser for Ozone House, to support their work with at-risk, marginalized, and LGBTQ teens. The show, which will take place at Woodruff’s, starting at 8:00 PM, is being hosted by Washtenaw Eviction and Foreclosure Defense (WEFD), and, from what I understand, a few tickets are still available. (Also on the bill are Japanther and Kev Choice.)

As for the interview, as you’ll soon discover, it’s not perfect. As I was picking Clementine up from school during the call, and as Boots was in the middle of a soundcheck, the quality of the audio isn’t great, and, as a result, much of what was said was garbled. And, because of that, I’m sure that I made a few mistakes in my transcription. I’ve also slightly edited both my questions, and his answers, in hopes of making the transcript flow better. Those of you who would like to hear the interview live and unedited, though, with all of the awkward pauses, blasting organ music, screaming children, and inartful, half-developed thoughts (on my part) that lead nowhere, can find the recording embedded at the bottom of this post… Enjoy.

MARK: I’ m curious about your background, if we can start there. I’ve read that you come from a long line of organizers… of “radical” organizers… I guess, in particular, your father. And I’m curious to know what got him involved in the Progressive Labor Party, and what took your family to Oakland, after having started out in Chicago, and then lived in Detroit for a while.

BOOTS: So, the exact details would be something you’d have to get from him, but he started out in the civil rights movement, in the NAACP, in the 50′s. He worked on the organization of the first sit-down strikes, at the coffee shops in Greensboro, North Carolina. And, later on, he was in CORE (Congress of Racial Equality). And CORE moved him out to San Francisco. And he got involved in SDS and the Progressive Labor Party (PL) at that time, just before the San Francisco State strike, which led to the creation of the College of Ethnic Studies, and all of that happened. Then the Progressive Labor Party moved him and my mother out to Chicago to be involved there. And then they needed a full-time organizer for Detroit. So he moved, and took that spot, and was a full-time organizer for the Progressive Labor Party in Detroit.

MARK: Trying to organize inside the auto plants?

BOOTS: Yeah, that was some of it. I was very young, so I don’t know exactly, but there was some auto plant work, and some student work. All I remember is that there were a lot of parties at my house, which I found out later were meetings.

MARK: What do you remember of your time in Detroit? I know you were really young, but…

BOOTS: There’s a woman who’s still active around there named Barbara Ransby. She was a teenager who was always coming through. I remember my father coming hoome with his ribs bandaged up, because the Klan had tried to make a come-back in Detroit, or something like that. And they went out and fought the Klan. And he got billy clubbed by the police, or somebody got him in the back, while they were fighting. So I remember that picture of him having bandaged ribs. What I also remember is that there were a lot of big parties, with people talking a lot, with their legs crossed. I was six when I moved away from Detroit, but those are the things that I remember. I remember Ohio Players records being played a lot.

MARK: A lot of kids rebel against their parents, but it sounds as though you kind of followed in your father’s footsteps, at least with regard to your association with the Progressive Labor Party.

BOOTS: Well, to a certain extent, (joining the Progressive Labor Party) was something of a rebellion, in a sense… (My father, Walter Riley) left Detroit to become a lawyer, and he split with the Party. But some of the family friends were still folks in the Progressive Labor Party. There was a political split, but there were still friendships. And, so, by the time that that I was eight, he wasn’t in PL anymore. And I started getting involved with the Party when I was fourteen. And that’s like a lifetime, those six years between eight and fourteen. And he actually did not want for me to be involved, not because of the political differences… I think, later on, as I became more developed, it had to do with political differences… but, at the time, he was arguing with them, saying, “When I was leading the Party, we never would have let someone like him (me) in. He hasn’t read enough.” You know, he felt that they were being opportunist, for letting me in just because I wanted to be in. And, to be honest, it was in the 80′s when there wasn’t much going on. I think a lot of political organizations were happy with anything… so they were a little more liberal.

MARK: Yeah, you want young people with energy, so you bend the rules a bit, right?

BOOTS: Yeah… So I became involved in their summer projects, like helping to built an anti-racist farmworkers union (in California), an undertaking which was mainly being led by people who had been kicked out of the USW (United Steelworkers), for being Communists, and being militant… who then joined the Progressive Labor Party. So I learned a lot being there.

MARK: What’s your ongoing role with the Party now? Are you still involved?

BOOTS: I’m 41 and I haven’t been involved in about 21 years.

MARK: So you left at about the same age as your dad?

BOOTS: No, he was probably 30-somethng when he left.

MARK: You still identify as Communist, though, right?

BOOTS: Yeah… So, I had ended up being a part of (their) Central Committee meetings. And a lot of the people who I met through that were the folks who had created the Progressive Labor Party, who had split off from the Communist Party in the 50′s. And their take on how to organize, combined with some British folks who had been union organizers, who had moved to the U.S. and joined the Progressive Labor Party… They taught me a lot… My experience in the Party was… The way that they organized at the time – with the exception of the work with the farmers union – was more of a one-on-one thing. It was more like a religion. Our meetings would be about who we had talked to that day, and how close they were to the ideas of the Party. “This is not going to get anywhere,” (I thought). I was in there from the age of fourteen to the age of nineteen or twenty, and I was supposedly in the leadership, and I had ideas that were more about broadening things, and making us known to the people who lived around us. But my ideas were always sort of poo-pooed and argued against. What I realized was that a lot of those folks who were still around in the Party weren’t the folks that where great organizers, who had been involved before. You know, a lot of times, folks who are great organizers have an idea that tells them… they know that you have to shape the aesthetic of your message to best suit what works. That’s what great organizers do. That’s what good conversationalists do. They communicate the essence of the idea, and the details of the idea, but they don’t have to be stuck in one tactic, or one mode. So I feel like what was going on then, and it’s what’s been going on in a lot of organizations since then. People are tied to an aesthetic. They’re tied to a tactic. You know, I was told a lot of really strict rules for how organizing works. They weren’t really true. They were just basically what they did twenty years before.

MARK: Which I assume leads into why you adopted music. I mean, that was your new aesthetic, right?

BOOTS: Definitely. Yeah… I had been told in the organization that any art form that was created by Capitalism could not be used to make revolution, you know.

MARK: I read somewhere about you going around Oakland on a flatbed truck, doing guerilla hip-hop shows, on street corners… which, I guess, illustrates how you were getting away from the one-on-one approach that the Party had been pushing, and going into people’s neighborhoods and engaging them on their own terms, in their own language, right?

BOOTS: Exactly. There wasn’t a direct correlation between the two, though, because that happened in 2000. That was a development of a few circumstances… Prop 21 was being put forward.

MARK: That had to do with kids being prosecuted as adults, right?

BOOTS: Yeah. Exactly. And, I was teaching a workshop a the La Peña Cultural Center. So I decided to do something. The workshop was about art and organizing, so I decided to make it so that folks came and had to do something. We had a lot of young rappers involved, so that was the idea.

MARK: I’m curious as to how you balance stuff now. It sounds like, when you were coming up, a lot of the work that you did was really hands-on. You were in Oakland, working on really specific causes. You were drawing attention to specific cases of police brutality, and social justice issues, and making tangible contributions. And then you transitioned to a bigger stage, where the rewards are much different, and the pay off is a lot farther off. I’m curious as to how you juggle those two things. I know you’re still doing stuff on-the-ground in Oakland, but do you think you’ve got the mix right?

BOOTS: No, I don’t. I never have a good mix. It’s a struggle to figure out how to do both. Usually, I’m either doing one or the other. Like, when I was doing stuff with Occupy Oakland, I wasn’t doing music. Anything that you do right is going to take a lot of time. It’s hard to figure it out. I think the best way that I’ve figured out is just to have different time periods during the year where you work on different things. But it’s still not easy to work out. But, you know, I hear about people who can multitask and do those sorts of things, but, the way that I write, I’m not able to do that.

MARK: Do you think, over the last twenty years, you’ve kind of figured out how you’re of the most use to the cause?

BOOTS: It changes.

MARK: How’s it changing now?

BOOTS: Well, the world changes… What allows me to keep doing my music is the thought that, these folks (doing other forms of organizing) are only reaching a very limited number of people, and my music can reach way more folks, so I need to keep doing this music, to talk to more people… but we’re in a period where certain kinds of organizing actually can grab the attention of more people than it has in the past. It’s not the same kind of organizing… I think we went though a period in the 90′s where the idea of political organizing was anything but labor related. And, now, we have a certain amount of confluence in those two realms, that I think is lending itself to a new situation.

MARK: There are definitely positive signs with regard to labor organizing. What just happened a few days ago with the Walmart walk-out strike was encouraging. But, at the same time, I think union membership is at an all time low, isn’t it?

BOOTS: It definitely is, but that has nothing to do with where people are at, and what they want to do. The reason membership is an an all time low is that the unions aren’t militant. People don’t see unions as being able to win fights. Here’s an example. Occupy Oakland, a couple of different times, shut down the port. People, wether they agreed or disagreed with us, know that that we can shut stuff down… We broached the idea of a fast food workers union in Oakland, with it being connected to Occupy Oakland. We got a tremendous response, with people being in favor. Why? Because people thought that we could win. And the reason they thought this was because they knew, whatever the case, business owners knew that Occupy Oakland could shut shit down. So, therefore, it could win. I don’t think that a lot of people have faith that unions can win. They don’t think that unions will take militant routes that can win. Like, you have to be able to keep out scabs, which means a certain amount of breaking the law. In this day and age, if you play by the Taft-Heartly laws, you’re also going to have a hard time winning. You’re probably going to lose. So it’s going to take a different set of rules to win.

MARK: It’s kind of a difficult subject to broach, but I’m curious on your thoughts concerning militancy, and how far people should be willing to go. You’ve got songs like The Guillotine and Five Million Ways to Kill a CEO, which clearly allude to violence…

BOOTS: It’s symbolic…

MARK: Yeah, but it hints at a threat, right? It reminds people that, if they push folks too far, they’re going to pay a price.

BOOTS: Yeah, but militancy doesn’t only have that narrow definition. A militant movement is one that, at the drop of a hat, will shut things down… Let’s say this. The longshoremen are the most militant of the traditional unions that exist. The ILWU (International Longshore and Warehouse Union). Any time there’s a dispute, they’re down to shut the place down. That’s militant. They’re not waiting for it to be OK’d through arbitration. They’re showing their force, right away, and exacting a cost. Many of these unions will be involved in a fight and not want to strike right away. They’re scared about a number of things. Because of that, many people feel betrayed by their unions. They feel that they’re not going to be strong enough… that they’re not down for the fight. “Militant” implies that there are going to be actions, that may be physical, that allow one to win. And that means physically keeping out scabs. If you have a strike where replacement folks get brought in, the strike is usually over. Unions have to physically, forcefully, keep scabs out.

MARK: You mentioned that you were making some headway in Oakland with the fast food workers. What happened with that?

BOOTS: The main problem was convincing other folks in Occupy Oakland that it was something worthwhile compared to the other things that were going on. There are so many things going on with Occupy Oakland. People are spread really thin. So, it just wasn’t the time to bring this out. People weren’t down to dedicate the time.

MARK: It’s tough. It seems, with the Occupy movement, that so much time and effort is spent providing social services… like just recently, with all of the Occupy Sandy stuff. There are just so many needs that have to be addressed, that it takes up a lot of the bandwidth.

BOOTS: I think Occupy Oakland is different. It does provide services, but in the midst of campaigns. We’ve got the foreclosure defense stuff going on. And we’ve got various folks working on police brutality stuff. There are all sorts of things happening. Some people don’t want to do the service stuff and all, and, other people, that’s their thing. They like feeding people.

MARK: So it wasn’t a question of capacity. It was more a result of an internal discussion within the organization concerning priorities.

BOOTS:Yeah, a fast food workers union seems like a good idea, but the question is whether fast food workers would be down with it, and you’re not going to know unless you’re part of that outreach. And, at the same time, we had the school occupation happening, and a lot of people were involved in that. There were foreclosure defense actions. There were neighborhood assemblies. We were declaring moratoriums on foreclosure in certian neighborhoods. So, a lot of people were doing many different things. So, that was part of the problem at the time. Then there’s people that had experience organizing unions, and many of them wanted to be sure that it was their union that got to do it, and it was just too early to declare that. Let’s put it like this… It wasn’t for lack of wanting by people that were in fast food work. We actually had people that were down to do it, and we had a few things in place, we just didn’t have enough people to really carry it through.

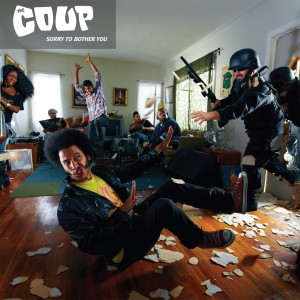

MARK: Speaking of the plight of low-paid workers, your new album, Sorry to Bother You

, is about telemarkting, and, in a broader sense, I guess, it’s about shitty, low-paying jobs in general. In addition to just being a good record, in the tradition of The Coup, is there a bigger message behind it? Are you trying to rally support for anything specific? Does either the album, or the movie that you’re working on, which uses the album as a soundtrack, touch on, for instance, the importance of organizing low-wage workers?

BOOTS: Not specifically around organizing telemarketers. The movie has some stuff about a union that’s being attempted at a telemarketing spot. Which is what was happening at the place that I worked at (when I was doing telemarketing). But it’s not specifically around organizing telemarketers. It’s around organizing people in the workplace in general.

MARK: So that message is in the movie?

BOOTS: Yeah. Yeah… Well, I don’t know that the “message” is in the movie, but the situation is in the movie.

MARK: Are you in pre-production yet for the movie?

BOOTS: I guess, technically, yeah.

MARK: Your producer, I’ve read, is Ted Hope, who produced movies like The Ice Storm, Happiness, American Splendor…

BOOTS: And 21 Grams. And the director is this guy, Alex Rivera, who did this movie called Sleep Dealer.

MARK: How’d it all come together?

BOOTS: I just kind of put a blast out to people I know, and Danny Goldberg, who was managing Street Sweeper Social Club, and also used to manage Nirvana and work with Led Zeppelin, read it and loved it. And he got it to Ted Hope. And Ted Hope was like, “I want to make this movie.” It probalby also helped that I had a soundtrack.

MARK: How did you sell them on the idea that you would be the right person for the lead? Or was that just part of the deal going in?

BOOTS: That was just part of the deal. I was like, “I’ve written this script. I have the soundtrack. And I will play the lead.” So, if somebody did’t like that, they just didn’t respond… It’s also a good marketing thing for them too. You know, if it’s going to be an independent film, there’s probably going to be more interest in it if the creator of it is part of it as well. I’m acting all the time anyway.

MARK: What do you mean… on stage?

BOOTS: Yeah, as a performer – it’s theatrical.

MARK: Had you attepted to do someting like this before? Didn’t I hear about a book that was being written from one of your songs, and the possiblity that it may turn into a film as well?

BOOTS: So a woman heard a song (Me and Jesus the Pimp in a ’79 Granada Last Night) and wrote a book based on it… I didn’t want the movie made. It had the potential to be a very terrible movie, if not done by the right person… I didn’t like the themes. She took the story and read things into that I…

MARK: With this new record, when you started writing it, did you know that you wanted to see it evolve into a dark comedy…

BOOTS: Well, I wrote the script first. I took like a year and wrote the script, while my manager, agent and record label said, “What are you doing?”

MARK: Because they wanted to keep you recording, and playing on the road…

BOOTS: Yeah. Yeah. It’s like, “You’re not going to get a movie made.” They wouldn’t say it in exactly that way, but that was the thought.

MARK: So, you think that it will do well in the marketplace… that people will buy tickets and like it?

BOOTS: Oh, yeah. There are people that have read it that I trust, that think that it’s a great, new, and interesting thing.

MARK: I’m happy for you… You put something out on Twitter a few days ago. “I realized five years ago,” you said, “we’re never going to go platinum, we’re never going to get radio play, we’re never going to make money at this.” Is part of this movie thing because you want to reach a wider audience, or is it more about paying the bills?

BOOTS: I don’t think people are able to pay bills on independent movies.

MARK: I imagine that you’d get a cut on video sales, right?

BOOTS: Yeah, but think about the time that you spent on it.

MARK: I guess what I was getting at is that it’s probably a little more lucrative than the record business.

BOOTS: Maybe for somebody. But independent movies? No. It’s not like that. It’s a labor of love. But people want to make some money at it. And that’s one thing about Ted Hope. He’s an independent movie guru. He’s someone who’s able to make independent film turn a profit. But, again, like I said, the amount of profit, compared to the amount of time put into it… It’s not like some cash cow. But it’s possible, you know. Maybe it could be some breakout hit. But it’s not real likely to happen. And that’s the name of the game in every industry. “More work for less pay.”

MARK: I’m curious as to where you draw the line. You mentioned earlier that folks in the Progressive Labor Party had told you that no artistic endeavor could come out of the Capitalist system and have any meaning, or something along those lines. And you pursue this line as a career. But you draw a line at advertising…

BOOTS: I didn’t believe them (that nothing good could come from works produced within the system)… In reality, that’s where music comes in. It’s advertising. Music is licensed to TV shows. It’s advertising. TV shows are there to keep people watching, so they’ll watch commercials. So, the music that’s licensed to them helps that to happen. And we do that.

MARK: Yeah. You’ve done that. You’ve written music for the Simpsons, and done other stuff. But yet, when it comes to selling a song to Levi’s, you’ve said something like, “That’s a line that I won’t cross.” And I’m curious about that line, and where you draw it. Like you say, the TV show is there to sell ads, and you work with them. So, that line is kind of fuzzy… I’m just wondering what your thought process is. Do you consider, for instance, the good stuff you could do with the money that you’d receive from selling a song to a company, or the fact that it would get your music out to a broader audience? I guess what I’m asking is, how firm is that line?

BOOTS: Well… For instance, K-Mart offered us a bunch of money for the Magic Clap. They wanted to make it a part of their main commercial ad campaign for the fall. So, you’d turn on the TV, and you’d hear, “K-Mart, Magic Clap,” forever. And you’d think of K-Mart when you hear that song. And do I want to spend my life with that? Like, the job market is hard out there, but… That would erase a lot of shit, you know? If I were going to try to make money, I could probably think of some other things to do, that weren’t music-related. If I did that, though, I’d reach more of an audience, but people would be thinking of that song, or whatever it is, as connected to that group. So, you know, when they offer The Coup money, they’re not only offering The Coup that. They’re buying a group. They’re buying an idea, you know? The idea that, “Even these dudes, are behind this product.”

MARK: So they’re buying your credibility…

BOOTS: It’s the idea that people think that we represent (the company or product). They’re buying philosophy. If I was just an artist known for making… Let’s say that I had my same revolutionary ideas, but that my art, that I was know for, was acting, or making love songs, or whatever. Then, when I did something like that, it would just be about me. But for me to attribute those songs to a product, means to attribute those ideas… So, for instance, when I was in Portland, we did an eviction defense rally, people were marching down the street changing, “we got the guillotine.” So, lets’s say I turned around, and sold that song to Nike… It wouldn’t just be about me. It would be about a movement.

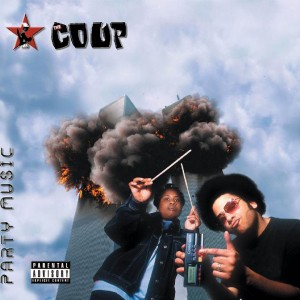

MARK: When I first heard about your band, it was right after 9/11, and the cover for your record Party Music became a news item. I’m just wondering if you were at all scared when that happened, when you saw what happened on 9/11, and then thought about the album cover that you’d just created, which showed you blowing up the World Trade Center using a guitar tuner… Were you afraid of a backlash?

BOOTS: You know, I got into the music to talk about ideas. So I really didn’t worry about it. It gave me a platform to talk about other ideas.

MARK: I know that Bill Maher gave you a hard time about it on his show, and he also, as I recall, said something about you being a Communist, like “people who sell records aren’t Communists.” Are you getting better at answering those kinds of challenges now, after having heard them for a couple of decades?

BOOTS: The idea of wanting to make a revolution… You have to be in the system to do it. You can’t say, “You can’t be a Communist and work retail.” If you work in an automotive factory, you’re participating in Capitalism, but how else do you organize anyone, if you’re not part of it? Folks that say stuff like that either don’t understand, or they’re looking for a quick retort. The reality is that what people are saying is not that they don’t want to participate, but that they don’t want other people to be affected. I don’t want other people to be affected by Capitalism. I feel that, in reality… and I may be deluding myself… I’m a pretty crafty dude. I can figure out how to survive. I could figure out how to be the crab that climbs up the barrel, or whatever. But I don’t want for there to be a barrel. I don’t want everybody else to get cooked. And that’s the point.

MARK: Do you think we’re making any progress? Things have gotten a lot worse in a lot of ways since you started in 1991. Wealth inequality, for instance…

BOOTS: Really? In 1991, we were having demonstrations with ten people. So, things have gotten a lot better. Now we’ve got thousands of people, all with the idea that we need a systematic change, with class analysis being a part of it. Things have gotten better.

MARK: I wasn’t thinking about the numbers of people in the street. I was thinking about wealthy inequality, the fact that our public schools are being systematically dismantled…

BOOTS: The numbers are the only thing that matters, though. What matters is not how the state is working, or how the system is working, but the point at which the movement is that could change the system.

MARK: I can see you point, and there’s potential there. A movement is starting to build. But, at the same time, you see the public school system being systematically taken apart, our wealth being siphoned off by for-profit charter schools, the growing, racist “patriot” movement in America…

BOOTS: Yeah, and all of those things are going to happen as long as we don’t have a movement. So none of that surprises me. As long as you don’t have a movement, any of the gains that you make are going to be dismantled. And that’s why a revolutionary movement that fights for reform, on the way to making revolution, and sustains the movement… That’s why you chart your progress relative to how the movement is growing, not on how strong the system is that is attacking you.

MARK: One last question… Were do we have the most leverage? Where should we be focusing right now, if we really want to make long term, systematic, sustainable change?

BOOTS: Well, it’s like we were talking about earlier. I think right now what people want are material gains. They need to see victories. And they need to see it done in a certain way. We need a radical, militant labor movement that uses direct action and work stoppages to gain some of these things. We need for it to be connected to the community, and not just built around wages. But using labor and work stoppages to effect change in other areas, that would normally be considered community things – community organizing. An example is how the ILWU shut down the port of Oakland in protest of the Oscar Grant verdict. They might have done it in a safe way, but that’s an example. And there need to be sympathy strikes. That’s got to become a tool. And union leaders are going to have to be down with going to jail, just like anyone else on the line is down for it…

Now here’s the recording, for those of you who either can’t read, or just refuse to.

A big thank you to my friend Jeff Clark for reaching out to Boots, and making all of this happen. And thank you to all of you who contributed via Kickstarter to bring the vision to reality.

See you Sunday night.

MARK: I’ m curious about your background, if we can start there. I’ve read that you come from a long line of organizers… of “radical” organizers… I guess, in particular, your father. And I’m curious to know what got him involved in the Progressive Labor Party, and what took your family to Oakland, after having started out in Chicago, and then lived in Detroit for a while.

MARK: I’ m curious about your background, if we can start there. I’ve read that you come from a long line of organizers… of “radical” organizers… I guess, in particular, your father. And I’m curious to know what got him involved in the Progressive Labor Party, and what took your family to Oakland, after having started out in Chicago, and then lived in Detroit for a while. BOOTS: Yeah… So, I had ended up being a part of (their) Central Committee meetings. And a lot of the people who I met through that were the folks who had created the Progressive Labor Party, who had split off from the Communist Party in the 50′s. And their take on how to organize, combined with some British folks who had been union organizers, who had moved to the U.S. and joined the Progressive Labor Party… They taught me a lot… My experience in the Party was… The way that they organized at the time – with the exception of the work with the farmers union – was more of a one-on-one thing. It was more like a religion. Our meetings would be about who we had talked to that day, and how close they were to the ideas of the Party. “This is not going to get anywhere,” (I thought). I was in there from the age of fourteen to the age of nineteen or twenty, and I was supposedly in the leadership, and I had ideas that were more about broadening things, and making us known to the people who lived around us. But my ideas were always sort of poo-pooed and argued against. What I realized was that a lot of those folks who were still around in the Party weren’t the folks that where great organizers, who had been involved before. You know, a lot of times, folks who are great organizers have an idea that tells them… they know that you have to shape the aesthetic of your message to best suit what works. That’s what great organizers do. That’s what good conversationalists do. They communicate the essence of the idea, and the details of the idea, but they don’t have to be stuck in one tactic, or one mode. So I feel like what was going on then, and it’s what’s been going on in a lot of organizations since then. People are tied to an aesthetic. They’re tied to a tactic. You know, I was told a lot of really strict rules for how organizing works. They weren’t really true. They were just basically what they did twenty years before.

BOOTS: Yeah… So, I had ended up being a part of (their) Central Committee meetings. And a lot of the people who I met through that were the folks who had created the Progressive Labor Party, who had split off from the Communist Party in the 50′s. And their take on how to organize, combined with some British folks who had been union organizers, who had moved to the U.S. and joined the Progressive Labor Party… They taught me a lot… My experience in the Party was… The way that they organized at the time – with the exception of the work with the farmers union – was more of a one-on-one thing. It was more like a religion. Our meetings would be about who we had talked to that day, and how close they were to the ideas of the Party. “This is not going to get anywhere,” (I thought). I was in there from the age of fourteen to the age of nineteen or twenty, and I was supposedly in the leadership, and I had ideas that were more about broadening things, and making us known to the people who lived around us. But my ideas were always sort of poo-pooed and argued against. What I realized was that a lot of those folks who were still around in the Party weren’t the folks that where great organizers, who had been involved before. You know, a lot of times, folks who are great organizers have an idea that tells them… they know that you have to shape the aesthetic of your message to best suit what works. That’s what great organizers do. That’s what good conversationalists do. They communicate the essence of the idea, and the details of the idea, but they don’t have to be stuck in one tactic, or one mode. So I feel like what was going on then, and it’s what’s been going on in a lot of organizations since then. People are tied to an aesthetic. They’re tied to a tactic. You know, I was told a lot of really strict rules for how organizing works. They weren’t really true. They were just basically what they did twenty years before. BOOTS: Yeah, but militancy doesn’t only have that narrow definition. A militant movement is one that, at the drop of a hat, will shut things down… Let’s say this. The longshoremen are the most militant of the traditional unions that exist. The ILWU (International Longshore and Warehouse Union). Any time there’s a dispute, they’re down to shut the place down. That’s militant. They’re not waiting for it to be OK’d through arbitration. They’re showing their force, right away, and exacting a cost. Many of these unions will be involved in a fight and not want to strike right away. They’re scared about a number of things. Because of that, many people feel betrayed by their unions. They feel that they’re not going to be strong enough… that they’re not down for the fight. “Militant” implies that there are going to be actions, that may be physical, that allow one to win. And that means physically keeping out scabs. If you have a strike where replacement folks get brought in, the strike is usually over. Unions have to physically, forcefully, keep scabs out.

BOOTS: Yeah, but militancy doesn’t only have that narrow definition. A militant movement is one that, at the drop of a hat, will shut things down… Let’s say this. The longshoremen are the most militant of the traditional unions that exist. The ILWU (International Longshore and Warehouse Union). Any time there’s a dispute, they’re down to shut the place down. That’s militant. They’re not waiting for it to be OK’d through arbitration. They’re showing their force, right away, and exacting a cost. Many of these unions will be involved in a fight and not want to strike right away. They’re scared about a number of things. Because of that, many people feel betrayed by their unions. They feel that they’re not going to be strong enough… that they’re not down for the fight. “Militant” implies that there are going to be actions, that may be physical, that allow one to win. And that means physically keeping out scabs. If you have a strike where replacement folks get brought in, the strike is usually over. Unions have to physically, forcefully, keep scabs out. , is about telemarkting, and, in a broader sense, I guess, it’s about shitty, low-paying jobs in general. In addition to just being a good record, in the tradition of The Coup, is there a bigger message behind it? Are you trying to rally support for anything specific? Does either the album, or the movie that you’re working on, which uses the album as a soundtrack, touch on, for instance, the importance of organizing low-wage workers?

, is about telemarkting, and, in a broader sense, I guess, it’s about shitty, low-paying jobs in general. In addition to just being a good record, in the tradition of The Coup, is there a bigger message behind it? Are you trying to rally support for anything specific? Does either the album, or the movie that you’re working on, which uses the album as a soundtrack, touch on, for instance, the importance of organizing low-wage workers? MARK: When I first heard about your band, it was right after 9/11, and the cover for your record Party Music became a news item. I’m just wondering if you were at all scared when that happened, when you saw what happened on 9/11, and then thought about the album cover that you’d just created, which showed you blowing up the World Trade Center using a guitar tuner… Were you afraid of a backlash?

MARK: When I first heard about your band, it was right after 9/11, and the cover for your record Party Music became a news item. I’m just wondering if you were at all scared when that happened, when you saw what happened on 9/11, and then thought about the album cover that you’d just created, which showed you blowing up the World Trade Center using a guitar tuner… Were you afraid of a backlash?